What is combat robotics?

Combat robotics is weight class based robotics competition in which teams design robots that fight to the death, incapacitation, or end of a timed round round, whichever comes first. Like in many traditional sports, the robots are divided into different weight classes typically ranging from Fairyweight robots (0.33lbs/0.15gk) up to Heavyweight and Alternative Heavy weight robots (220lbs/100kg or 250lbs/110kg respectively). Aside from matches where one of the competitors is destroyed or incapacitated, match winners are determined by judges that score each robot on a variety of catergories weighted, typically, aggression (3 points), control (3 points) , and damage (5 points).

Check out the Instructional Design Page for the basics of bot building! *Please see the Battlebots - World Championship VII page for more information about Alternative Heavy Weight Robots

My Builder Philosophy

Build something ridiculous and share the knowledge.

Every bot I have designed, I have looked for ways to cause passerbyes to do a double take and have kids yell "WHAT'S THAT?!". This often leads to more technical questions that are driven by curiosity and excitement from people that would otherwise not be interested in robotics. When something catches your eye, curiosity takes over and you want to learn more, even if the topic is somethng you know nothing about.

No one goes into combat robotics knowing exactly what they are doing. Even with a background in engineering, there is still a steep learning curve. Robots are using components in ways they were never designed for and pushing them to their limits. By sharing what we have learned and discovered with our respective bots, we are able to lower the barrier to entry and develop better, more destructive bots and more fun competitions.

Competitions

The competitions that I have most often competed in are Robobrawl, a 30lb Feather Weight, competition, and Design. Print. Destroy. (DPD), a 3D printed 1lb Ant Weight competition. Both of these competitions take place at the University of Illinois and are run by students and draw in competitors of all levels.

When I was attending the University of Illinois, I helped create Design. Print. Destroy (DPD). This competitoin is unique in that it is exclusively a 3D printed competition meaning that the only parts of your robot that are allowed to be metal/other materials are you electronics, wheels, fasteners, and no more than 50% of your weapon. These rules were created intentionally to lower the financial and manufacturing barriers that often prevent people from creating robots in addition to creating a more approachable competition to less experienced builders. DPD has expanded from being just a competition to becoming the main event for Robot Day, an outreach event hosted by students for local kids and families to learn about engineering.

1 lb Robots (Antweight Class)

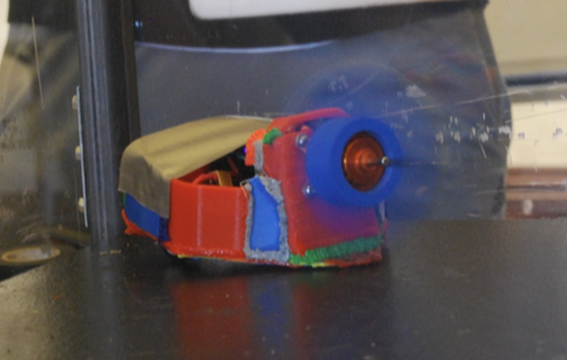

Taste the Rainbow

- 3rd Place Finish

- Robot Type: Freeform Spinner, akin to a biplane propellar

- Competition(s): Design Print Destroy (Spring 2019)

- Primary Body Material(s): 3D Printed ABS Scraps, 3Doodled ABS

Taste the Rainbow was a freeform spinner built entirely from scrap parts that otherwise would have gone in the trash. The robot is composed of failed 3D printed parts from other robots, waste ABS filament, electronics and screws recovered from destroyed robots, and the tape holding all of the electronics in which was used on a box to ship parts to our workshop.

I created this bot the night before the competition with only a 3Doodler pen in hand as a challenge to myself to see what I could create with only the parts that I had immediately on hand. In creating this bot, I sketched the base plate on a piece of paper and created the outline with a 3Doodler pen, I then used the pen effectively as a very weak ABS MIG welder to fill in the base plate with whatever fillament waste I had on hand. The variety of colors in the base plate is where the name is from as I thought it looked like a bunch of squished Skittles. Once the base plate was complete collected failed 3D printed parts and aligned them with the base plate and attached them again using the 3Doodler as an ABS MIG welder.

Kornizontal Spinner

- 1st Place Finish

- Robot Type: Horizontal spinner

- Competition(s): Design Print Destroy (Spring 2017)

- Primary Body Material(s): 3D Printed ABS

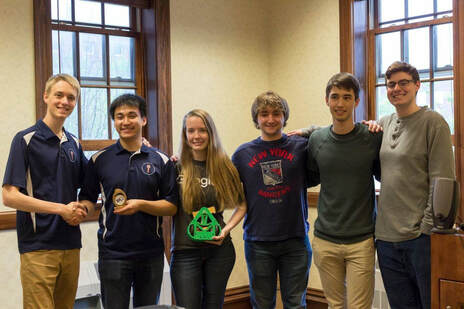

Teamwork!

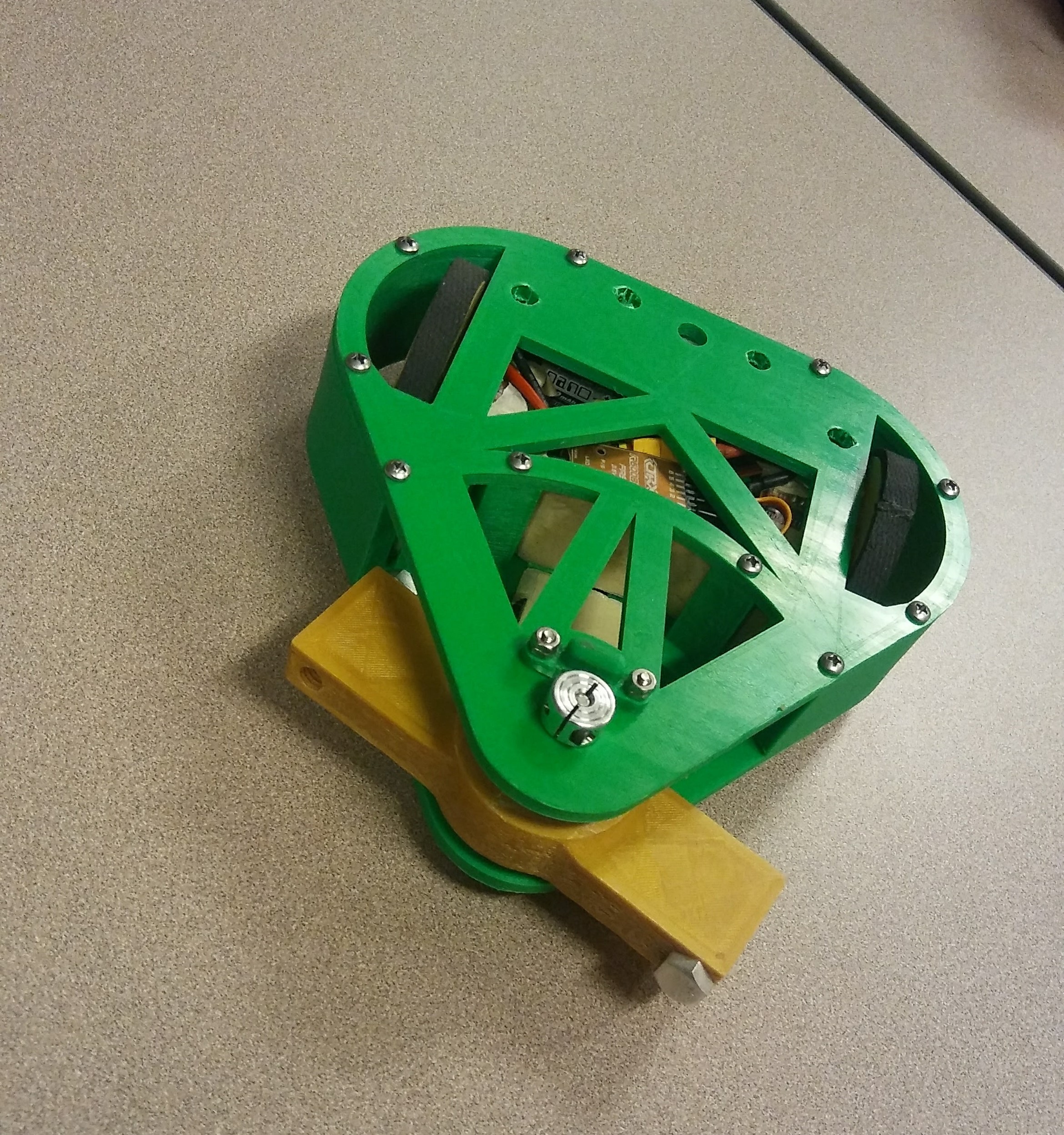

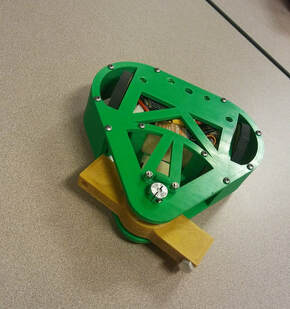

- Robot Type: Vertical Spinner (Egg Beater)

- Competition(s): Robot Day 2019

- Primary Body Material(s): 3D printed ABS

Oatmeal Razin’

- Robot Type: Vertical Spinner (Disk spinner)

- Competition(s): Robobrawl 2022

- Primary Body Material(s): 3D printed PETG

30lb Robots (Feather Weight Class)

All of the feather weight robots listed below were competed with my team, The Killer UniKorns. I was elected team captain 2016-2020, throughout our 4 years of undergrad. Within that time we competed 3 distinctly different robots with our fourth and final season having an unexpeted early end in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 Pandemic.

As team captain I was responsible for the planning, budgeting, part purchasing, and all paperwork that was required for my team, the university, and competitions. I was also responsible for my teams machining and safety training in our workshop and enforcing safety rules for not just my team but all of the teams sharing hte workspace. This included but was not limited to lathe work, milling, welding, soldering, and water jetting. I was also responsible for coordinating with the 10 other teams that shared our workspace for work time and to make sure that our workspace stayed clean and orderly.

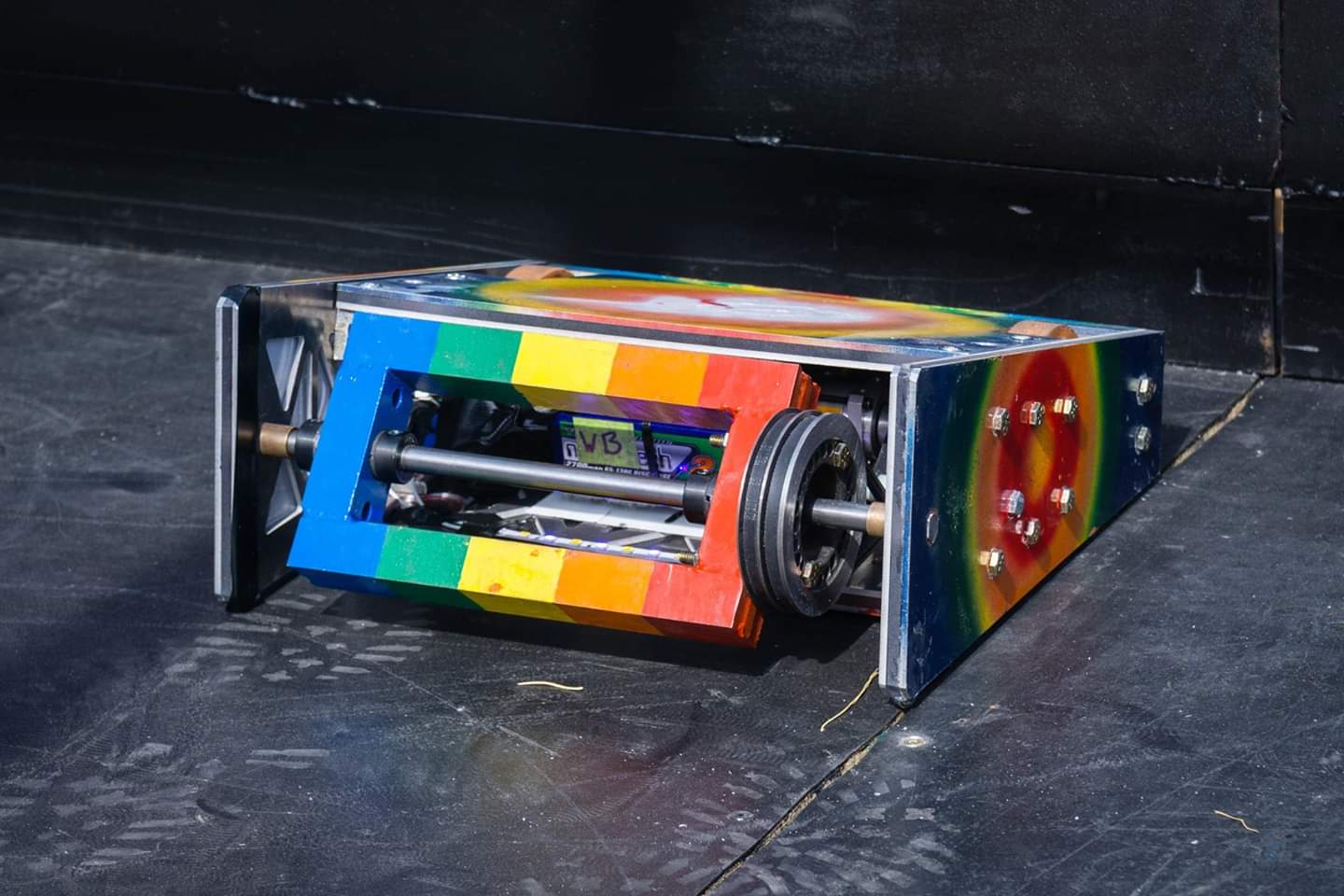

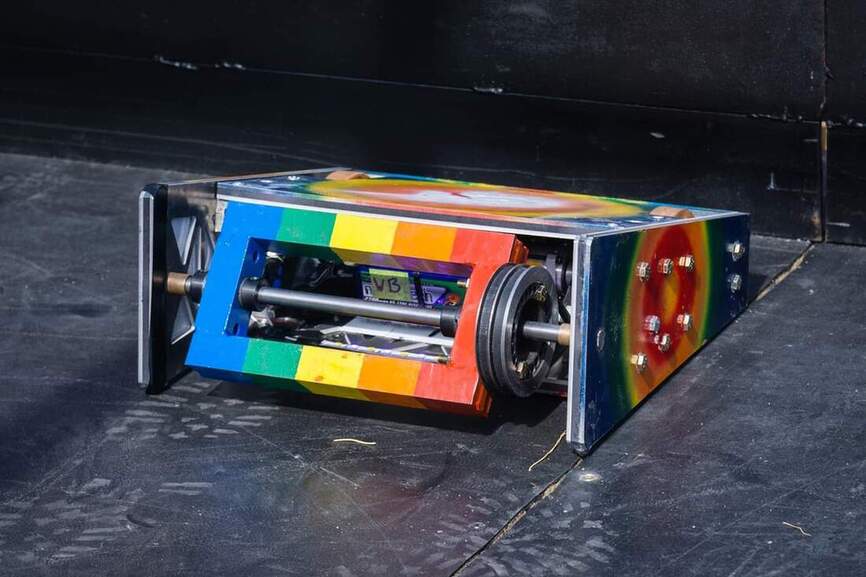

Rainbow Carnage

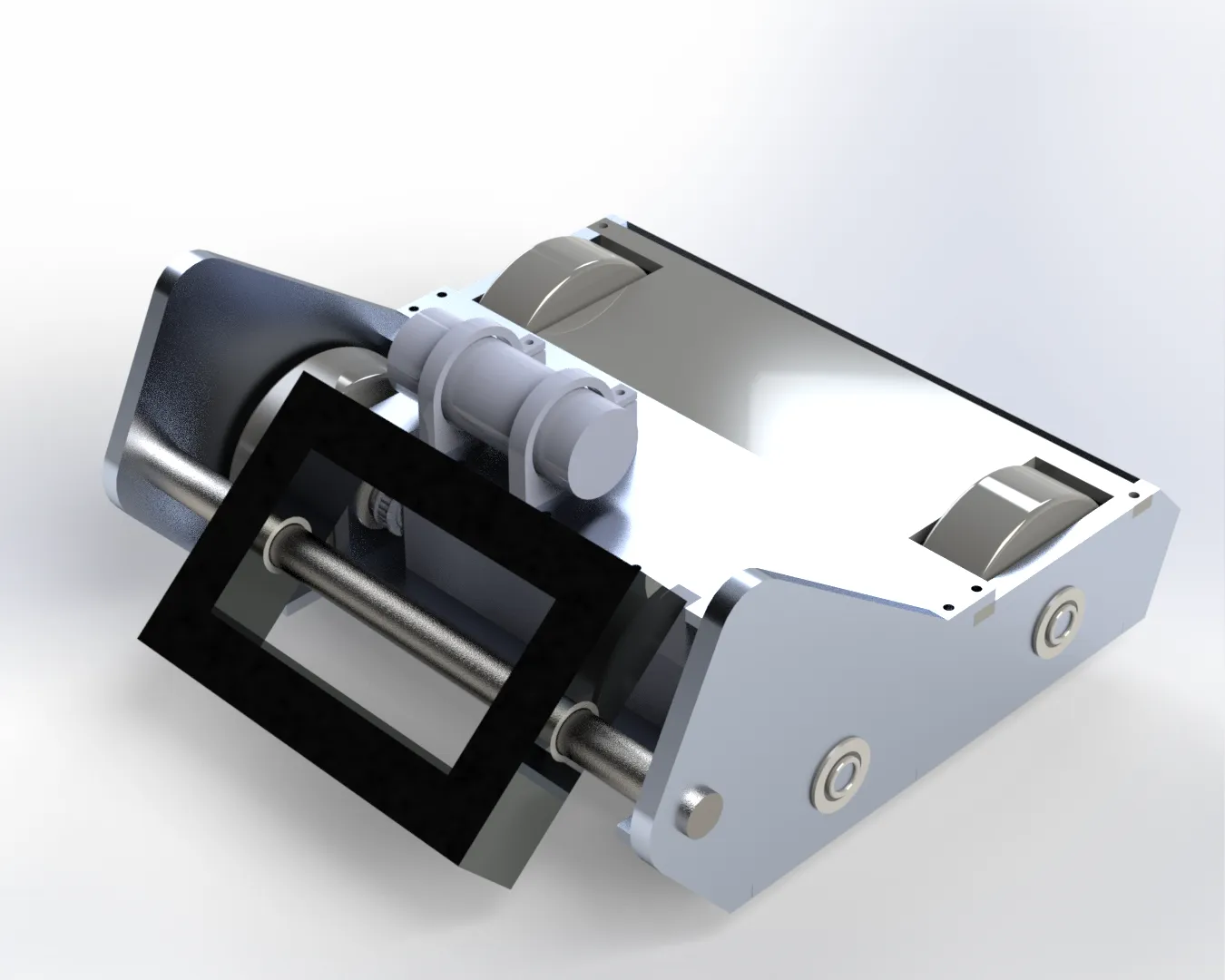

Unique characteristics: Dual timing belt run weapon, Composite armor, isolated weapon and drive circuits, rainbow paint job

Rainbow Carnage was a vertical spinner known as an egg beater/beater bar robot due to the the shape of its weapon. When spun up the weapon looked like an angry roll of life savers ready to eat some steel (see video). The weapon system used v-belts and cylindrical roller bearings pressed into the weapon allowing free rotation around the weapon shaft. This design enabled recoil on impact, preventing the weapon motor from stalling and minimizing the risk of self inflicted damage. The weapon was non heat treated waterjet cut S7 tool steel welded into a rectangular shape.

The robot’s frame was a composite of water jet cut polycarbonate sandwiched between two pieces of 7075 aluminum. The theory of the design was that the polycarbonate would allow for more flexibility when hit with a weapon than a solid wall of aluminum would allow while also weighing less. I painted the robot using a custom made lazy susanto achieve the even rainbow circles and the logo was painted after.

The bots electrical system had two isolated circuits each powered by seperate batteries for the tank drive and weapon systems. This setup ensured that if one circuit failed, the other would still be able to operate. Each circuit also contained a mechanical disconnect, in this case a push pull switch to open the circuit when the robot was not in operation.

What went well: The v-belts worked extremely well for controlling our weapon and allowing for slip where necessary The paint job was a hit and earned many compliments and children cheering for the unicorn bot during our matches We were able to maneuver well around a very uneven arena Our robot was robust enough to be tossed around the arena and continue fighting while only sustaining superficial damage

Lessons Learned: